NVIDIA Consolidates The AI Hardware Stack...And Competition

The recent $20 billion deal between NVIDIA and Groq was not a standard acquisition. If NVIDIA had attempted a full buyout, antitrust regulators at the FTC and DOJ would likely have intervened faster than Grok-4-fast completes a turn in your IDE (Grok the LLM, not Groq the hardware company). Instead, the companies structured a strategic agreement that includes a non-exclusive licensing of Groq’s architecture and an "acqui-hire" of Groq’s founder, Jonathan Ross, alongside the majority of his engineering team.

While Groq, the corporate entity, technically remains independent, NVIDIA has effectively absorbed the only architecture that posed a credible threat to its dominance in both model Training and Inference. There's several reasons why NVIDIA paid such a premium for a company with a fraction of its revenue, to really understand it we first need to dig into the silicon. Groq built a chip that operates on a fundamentally different philosophy than the GPU.

At Inference..

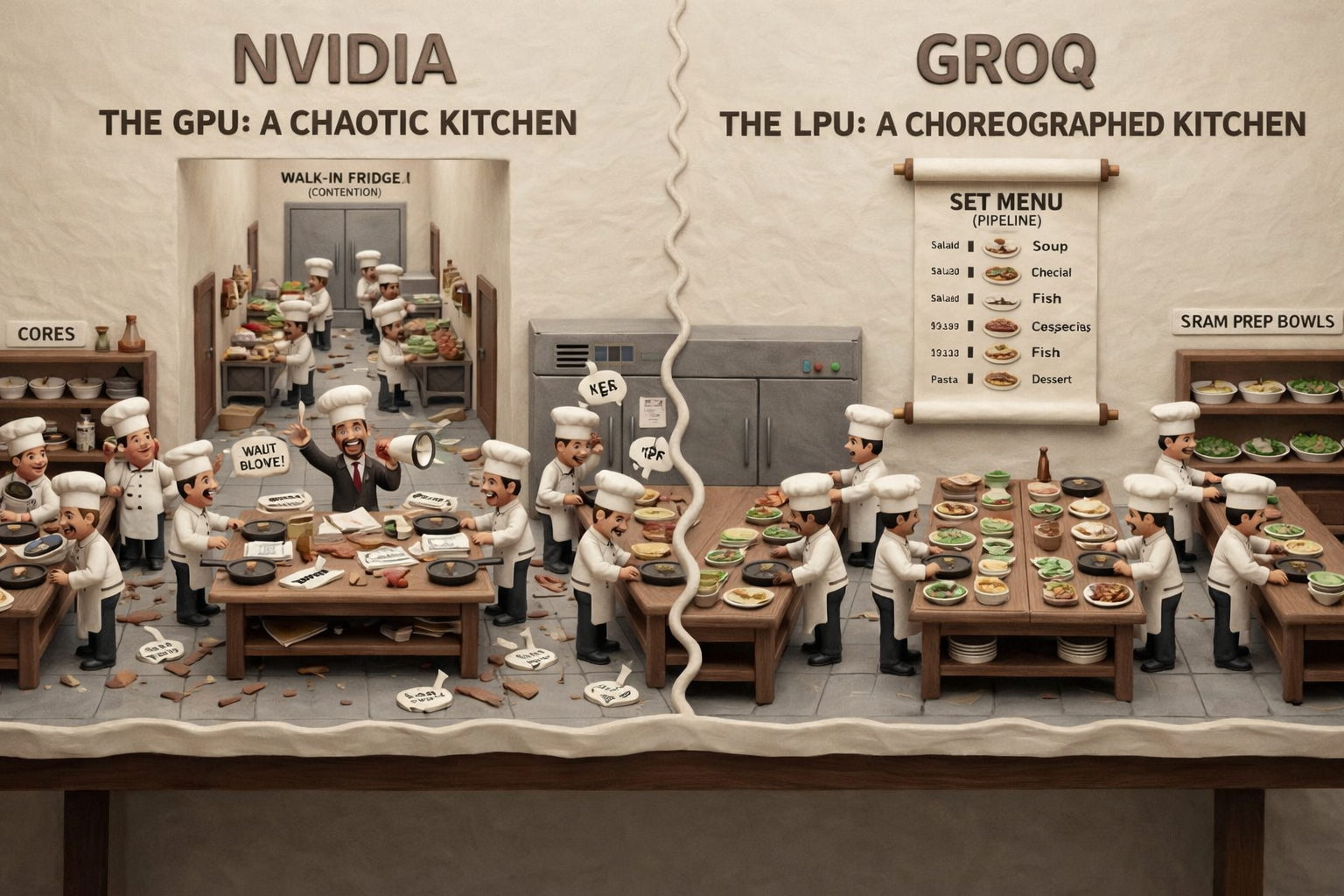

The GPU is a Chaotic Kitchen

NVIDIA’s GPUs are the undisputed standard for AI training because they are massive parallel processors designed to crunch terabytes of data to teach a model. However, for inference (the act of using the model to generate a response), GPUs introduce significant inefficiencies for exactly the reason they are great during training.

To visualize why, imagine a high-end, incredibly busy restaurant kitchen.

Kitchen Setup:

- The Chefs (Cores): Thousands of world-class chefs ready to cook.

- The Manager (Scheduler): A hardware scheduler stands at the front and shouts orders as they come in.

- The Walk-In Fridge (HBM): All ingredients are stored in a massive walk-in fridge down the hall, known as High Bandwidth Memory (HBM).

Chaos:

When an order comes in, the Manager calls it out and the Chefs react. They cannot cook immediately because they have to wait for runners to go to the Walk-In Fridge, find the ingredients, and bring them back. Sometimes the hallway is crowded, or two chefs reach for the same pan.

The Chefs are fast, but they spend a significant amount of time waiting. In computing, this is called latency. Unpredictable waiting time causes AI models to feel sluggish or inconsistent. The hardware reacts to the software in real-time, and that reaction time costs performance.

The LPU is a Choreographed Kitchen

Groq’s Language Processing Unit (LPU) redesigns the workflow to remove chaos using an architecture they call "deterministic."

Kitchen Setup:

- The Chefs (Cores): The same chefs are present, but their behavior changes.

- No Manager (Scheduler): There is no scheduler shouting orders. The hardware makes zero decisions during service.

- The Set Menu (Compiler): Instead of handling random orders, the service is a strictly pre-planned meal defined by the software.

- The Prep Bowls (SRAM): There is no walk-in fridge down the hall. Every ingredient is already prepped and sitting in small bowls right at the Chef's station, known as Static Random Access Memory (SRAM).

Choreography:

In this kitchen, the Chef doesn't wait for an order or a runner. The "Set Menu" dictates that at exactly 7:00:01 PM, the Chef will sauté the onions. The Chef reaches out at that exact second. Because the ingredients are in the prep bowl (SRAM) at arm's length rather than the distant fridge (HBM), the onions are there exactly when the chef needs them but only enough for a single meal.

In the GPU kitchen, the Chef is idle while the runner travels down the hall. In the Groq kitchen, that travel time is eliminated. There is no waiting. This allows the chip to run at maximum theoretical speed continuously, resulting in the instant text generation Groq is famous for.

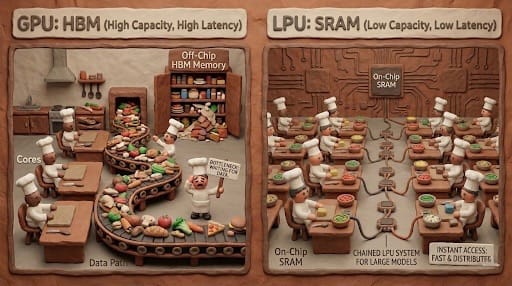

Speed vs. Capacity

The primary difference between the GPU and LPU architectures is how they handle memory.

- NVIDIA uses HBM (High Bandwidth Memory). HBM is dense and massive, making it excellent for storing the gigantic datasets needed to train models like GPT-5. However, it sits off-chip, which creates a bottleneck similar to the hallway to the walk-in fridge. It provides high capacity memory but results in higher latency.

- Groq uses SRAM (Static Random Access Memory). SRAM is incredibly fast because it is integrated directly onto the silicon. However, it is expensive and takes up physical space. A single Groq chip has very small memory capacity of roughly 230MB while the GPU has access to between 80–140 GB. To run a large model like Llama 70B, you cannot use just one chip; instead, you must chain hundreds of Groq chips together to act as one giant computer.

Why This Deal Matters

If NVIDIA is already the market leader, three primary drivers explain what, on the surface, appears to be an expensive licensing deal.

- Talent Acquisition

The most valuable asset in this deal is Jonathan Ross. Ross previously led the team at Google that invented the TPU (Tensor Processing Unit). He is one of the few silicon architects in the world who has successfully designed a chip that challenges NVIDIA’s paradigm. By bringing Ross and his engineering team in-house, NVIDIA neutralizes a competitor and integrates a different school of thought into their own roadmap. The move also prevents a scenario where a hyperscaler, like Meta or Amazon, acquires Groq to accelerate their efforts to move off NVIDIA hardware.

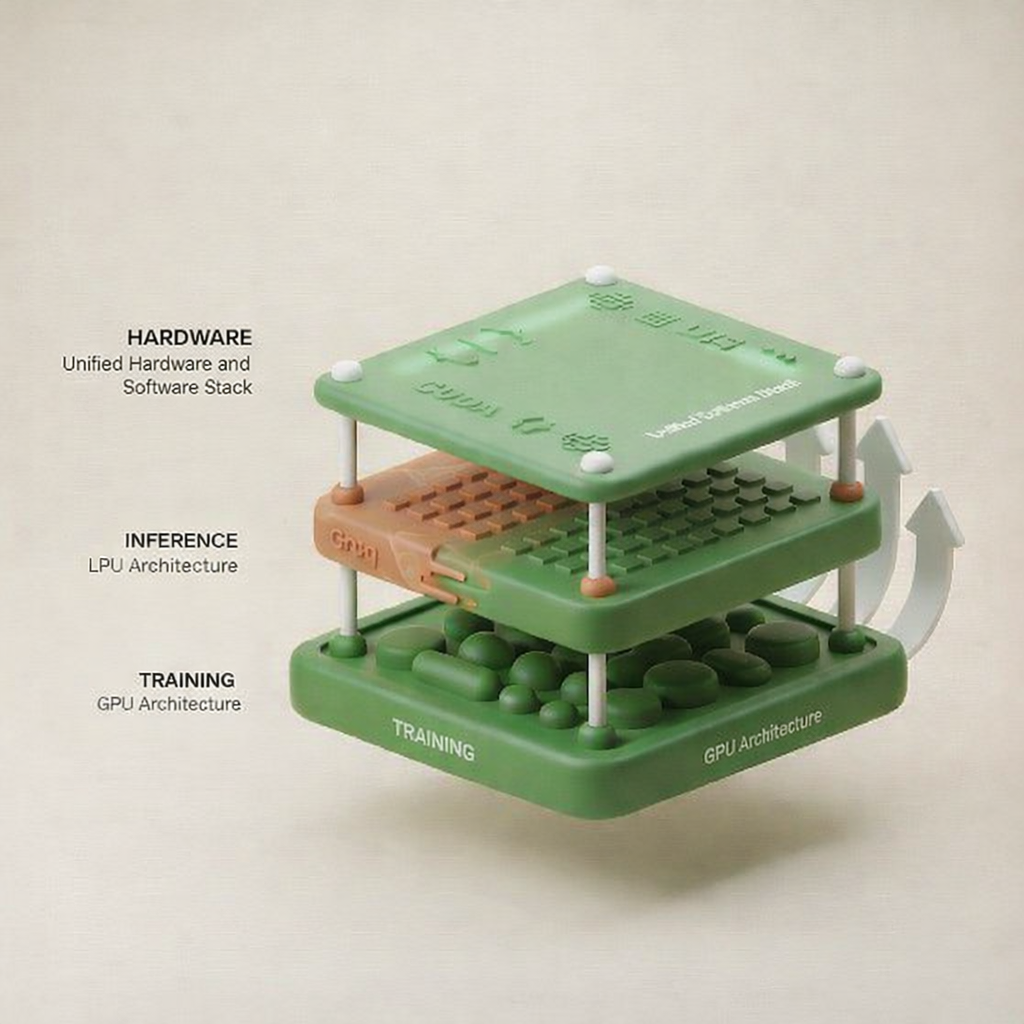

2. Dominating the Inference Market

For the last several years the AI hardware markets been defined by training, which required thousands of the high-memory GPUs to build models. AI adoption continues to increase in both the consumer and enterprise markets at the same time, causing a shift towards a focus on inference, or running those models for end-users. Inference requires different hardware optimizations than training; low latency and high throughput (tokens per second) are the new metrics of success. Groq specifically optimized their hardware for this. By licensing the technology, NVIDIA ensures they control the hardware stack for the entire lifecycle of an AI model, from training to inference.

3. The Shift to Software-Defined Hardware

NVIDIA’s primary defense has long been CUDA, its software layer. Groq took the concept of software-defined hardware to its logical extreme, where the compiler effectively controls the physical circuitry. This "compiler-first" approach allows for efficiencies that brute-force hardware cannot match. NVIDIA's likely to incorporate Groq’s compiler logic into future generations of their inference-specific chips to improve efficiency without sacrificing flexibility.

The Market Impact

This deal signals the lightning fast maturation of the generative AI industry. We've quickly moved past the experimental phase where raw power was the only metric that mattered. As enterprises begin to deploy agents and real-time voice assistants at scale, the cost and speed of inference become the bottlenecks to profitability. NVIDIA has effectively consolidated the market under their logo.

They now control the premier architecture for training (the GPU) and have absorbed the premier architecture for real-time inference (the LPU). This ensures that as the world moves from building AI to using AI, the infrastructure remains firmly in NVIDIA's hands.

Written by JD Fetterly - Data PM @ Apple, Founder of ChatBotLabs.io, creator of GenerativeAIexplained.com, Technology Writer and AI Enthusiast.

All opinions are my own and do not reflect those of my employer or anyone else.